I have not been having the very best time with technology lately. That’s not the newest thing, but when something I’ve been using with no particular problems for I-literally-can’t-remember-how-long suddenly decides I’m persona non grata, it’s hard not to take that personally.

The evening started like any other: doomscrolling and sharing the odd funny animal photo while chatting to a friend and browsing my many other open tabs, as you do. Only, suddenly Facebook developed a problem with me. An email, and the tab I had open to my account, informed me that my account had been suspended.

The only “explanation” I was given were two words: “account integrity.” By following that hyperlink, I got the general impression that something in my account, or something that I had shared, was deemed harmful. Facebook declined to inform me what material, exactly, this might have been.

The last post I shared was a photo of a tortoise with a baby tortoise on its head. It was adorable. In terms of understanding how I offended Facebook’s Community Standards so badly, I was precisely no better off.

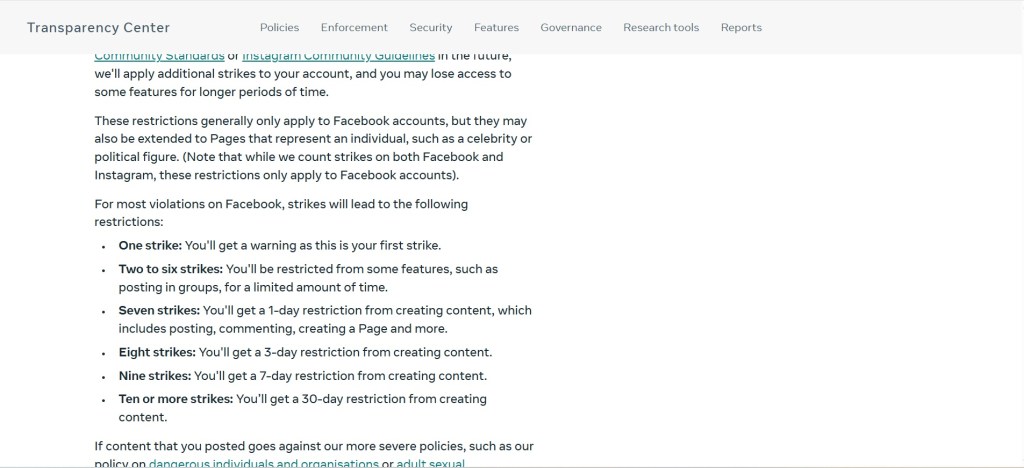

I was offered the chance to appeal… at least, that’s what Facebook calls it. However, I think most of us would imagine an appeal would involve the chance to speak in one’s own defence, or at least ask a single question. “What’s the problem?” for example. Facebook has a different understanding of the concept. After requesting an appeal and proving that I wasn’t a robot, I was told that my appeal was pending.

So, I went about my business (more tab browsing), telling myself everything was fine. This was clearly a misunderstanding. After all, I hadn’t done anything. I wasn’t impersonating anyone else: I hadn’t posted any content that anyone but a rabid fundamentalist would consider inflammatory. I share funny animal photos and cool facts about space, for crying out loud. An overzealous bot had probably flagged a random word out of context. As soon as a human being looked at it, this whole thing would be dismissed and I’d be back in business.

An hour later, I was told that my appeal had been declined, and to kindly quit darkening Facebook’s doorstep.

That was it. No explanation of what caused this decision, no explanation of the appeals process or why my appeal was declined, just “goodbye.” I can no longer log in or access anything Facebook-related. The emails I received were from no-reply accounts. I was given an option to download my information (again, no explanation of what that means), but using that link doesn’t appear to actually result in anything downloading. The only control I can now access is the language option. If rendering the information that my account no longer exists in Urdu would be helpful, I’ve got the goods. Otherwise, nada.

Some checking around reveals that I’m far from the only person who’s experienced something like this, and there doesn’t seem to be a way forward. Plenty of people have been booted off Facebook with no idea of why, and creating another account will only result in that being deleted too. It was from these people that I got the idea that my account may have been hacked – the forbidden content may have been in an Instagram account that was linked to my Facebook without my knowledge – but, obviously, I have no way of verifying that.

Luckily, the good people of Youtube were there to help me in my hour of need! A quick search resulted in a plethora of videos explaining what to do in situations like mine. The ones I viewed gave three basic methods to access Facebook’s customer service… two of which don’t apply to me as I’m not a business, just a person trying to use my account, and the third of which only led back to the same pages that didn’t explain anything before.

The general takeaway seems to be that the Facebook era of my life is over, and I’ll probably never know why. Those running Facebook do not seem to think they owe the people using their platform anything resembling care, a fair hearing, or simply not being punished for being the victim of cybercrime.

Perhaps I’m just naïve, but in my little world, if you don’t ask for someone’s point of view, you didn’t give them an appeal. And if you can’t be bothered to tell someone why you’re mad at them, you don’t have a reason.

This all leads me to consider a question that came up more than once in my search for information. Do I, at this stage, even want my account back? Why would I want to frequent a community – online or otherwise – that treats me this way?

There’s a pretty simple answer to that. Unfortunately, it isn’t that easy. Like most people, whole swathes of my life rest upon technology, because we’ve built a world where it’s just about impossible to get anything done otherwise. And, just now, the technology on which it all rests is looking a little shaky.

Is WordPress likely to delete this website if someone leaves a rude comment? Will Youtube kick me out if it doesn’t like the lyric video I look up for a song that’s stuck in my head? Am I going to log into AO3 one day to find my account gone, and never understand why?

Don’t get me wrong: I am all for tech companies taking responsibility for the content that is posted on their platform. However, “draconian” is not the same as “better,” and “penalising the victims of hacking” is not the same as “taking responsibility.” While Facebook’s account control people pat themselves on the back for their grand victory, the actual perpetrator will shrug and go hack someone else… and Facebook will probably delete them too.